How databases store data on HDD and SSD

February 15, 2026

Understanding how databases store table data such as rows and columns on disk forms the foundational groundwork for understanding how databases work internally. It helps us understand how indexes operate, how multi-level indexes are structured, and how B-trees and B+ trees efficiently store and access indexed data.

Let's see how it works below for HDDs, and then the similar concept applies to the SSDs.

Disk and Disk Structure

A disk is a non-volatile storage device used to store data persistently. Because it is non-volatile, the data on disk remains intact even when the system loses power (unlike RAM). This is why disks are essential for storing permanent files, databases, and operating system data.

Would highly recommend you watch this 3-minute YouTube video to get an idea of how an actual real HDD looks, so that you get a sense of what we are going to discuss in this article today.

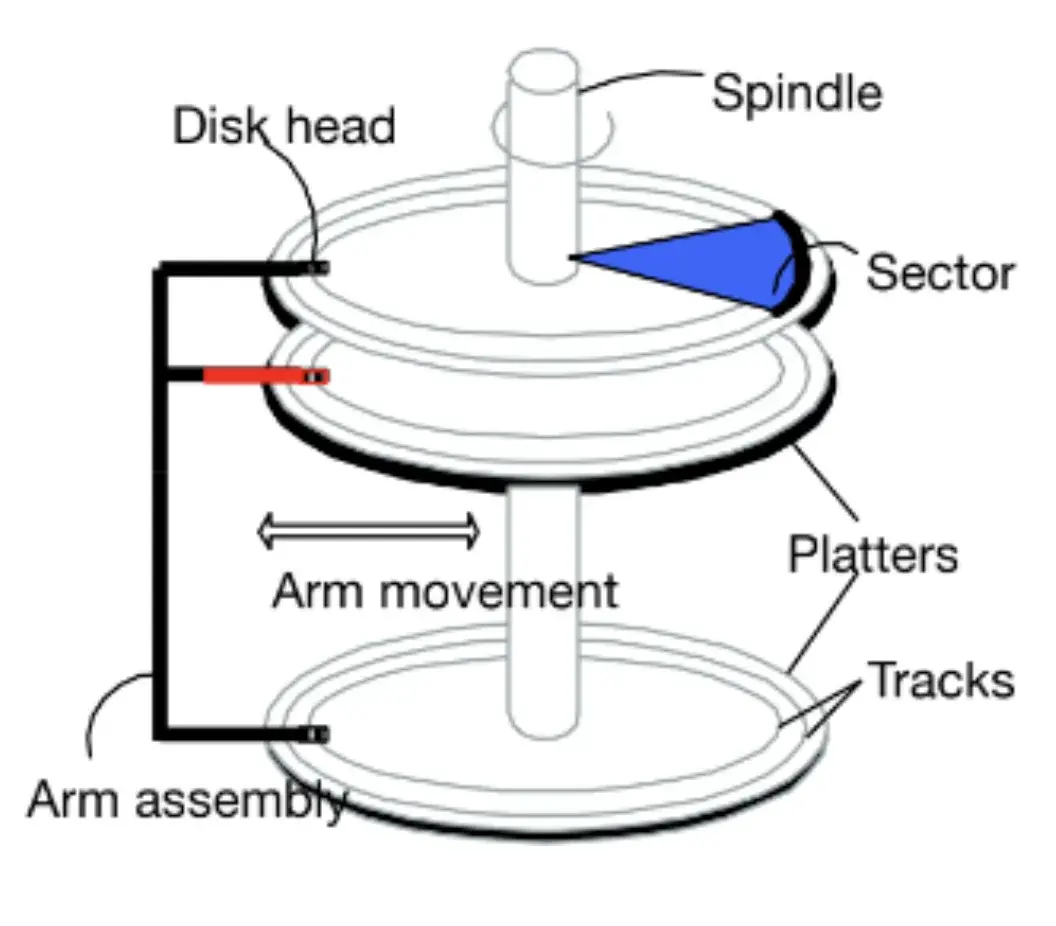

The disk is composed of the following components:

- Platters: Magnetic disks where data is recorded on both surfaces; and each surface is nothing but a set of concentric circles. (logic)

- Spindle (spindle motor): Rotates the spindle, which spins all the platters at a fixed RPM. (rotations per minute)

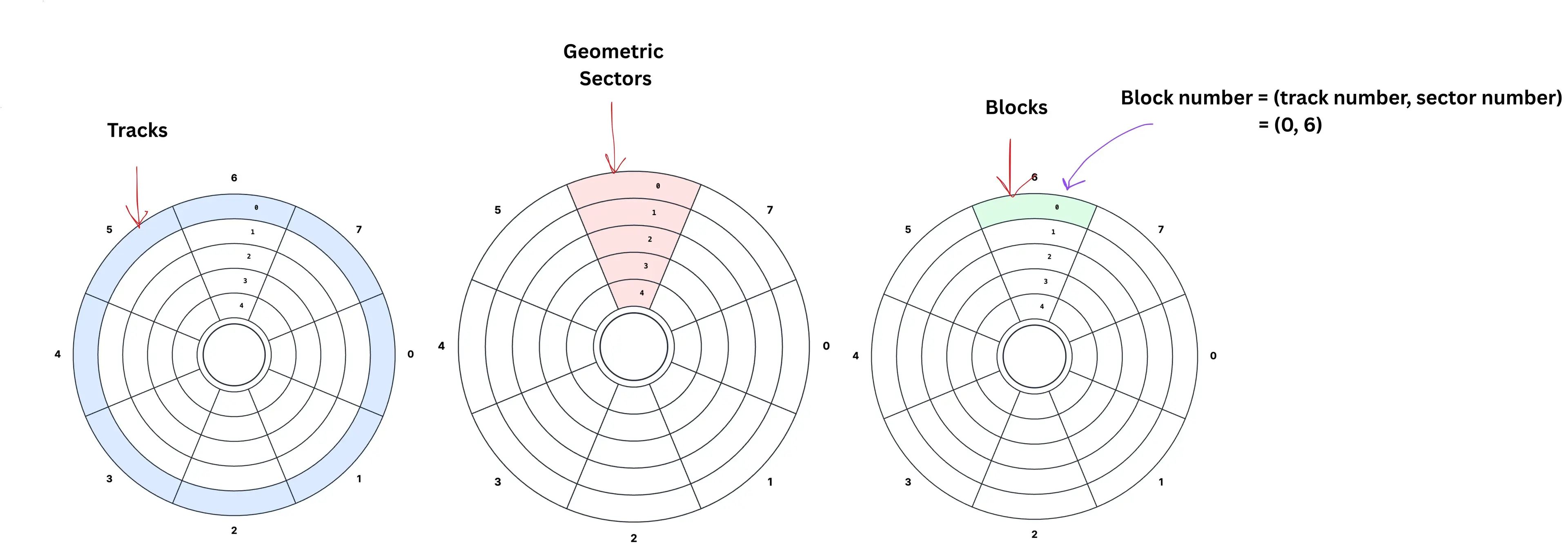

- Tracks: Individual concentric circular rings on the platter.

- Sector: This is a geometric sector, meaning just a portion of a disk. (shaped like a slice of pie.)

- Block (OS/filesystem block): The intersection of a track and a sector is called a block. Hence, any location on the disk, i.e., block address, can be identified by the track number and sector number. The block size is usually decided by the manufacturer. (earlier one block was around 512 bytes, now it is around 4KB+)

- Arm: Moves the read/write heads inward or outward to position them over the required track and sector.

How data is accessed from the disk?

Question: So how do we access the disk to read and write?

Answer: Well, we use disk APIs, which are OS-level system calls like read() and write() to read data from disk and write data back to disk.

Question: But how much data is accessed at a time?

Answer: At the OS/filesystem level, it doesn't like to deal with sectors etc, so data is transferred in blocks (usually 4 KB). Even if we ask for a few bytes, the OS typically returns the bytes that's contained in those 4KB blocks. Meaning it is the minimum amount of data which can be read/write by an I/O operation.

At the database level, the DB does not like to deal with these blocks, it thinks its too small a unit, so it works with pages (e.g., 8 KB / 16 KB). A page is the DB's logical unit, and it usually spans multiple blocks. So whenever we request data (using sql query for rows), the OS ends up fetching bytes from one block or a set of blocks (depending on how much we asked for). Meaning if the disk returns bytes from 2 blocks say 8KB, then the db considers it as 1 page of 8KB. (Let's solve an example together to get a clear understanding of this..)

As discussed, a data page is a fixed-size chunk (e.g., 8 KB) that the database reads from disk into memory. If the underlying disk block size is 4 KB, then one 8 KB page is stored across two disk blocks, so the OS reads two blocks to bring one page into RAM.

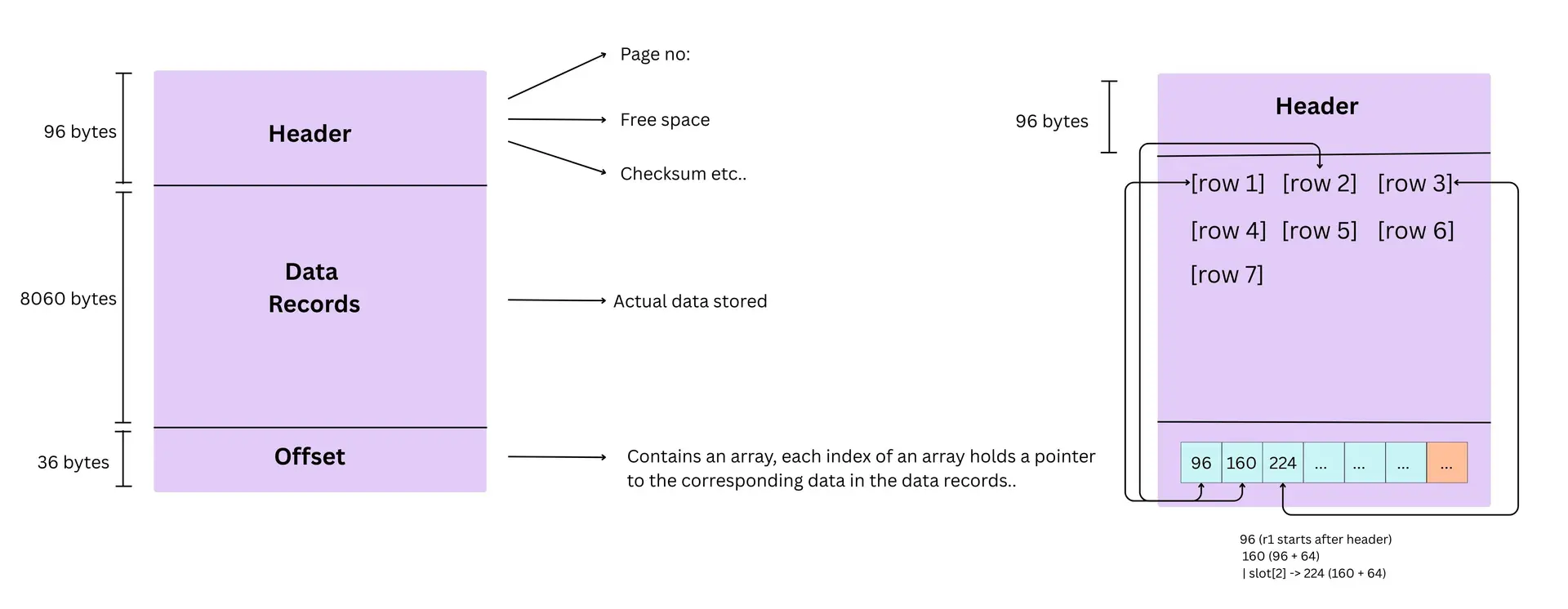

- The page starts with a header that stores metadata like page id and free space pointers.

- Actual rows are stored sequentially in the data area as bytes.

- At the bottom of the page is a slot directory, which is an array of offsets. Each slot entry stores the byte position where a particular row begins inside the page.

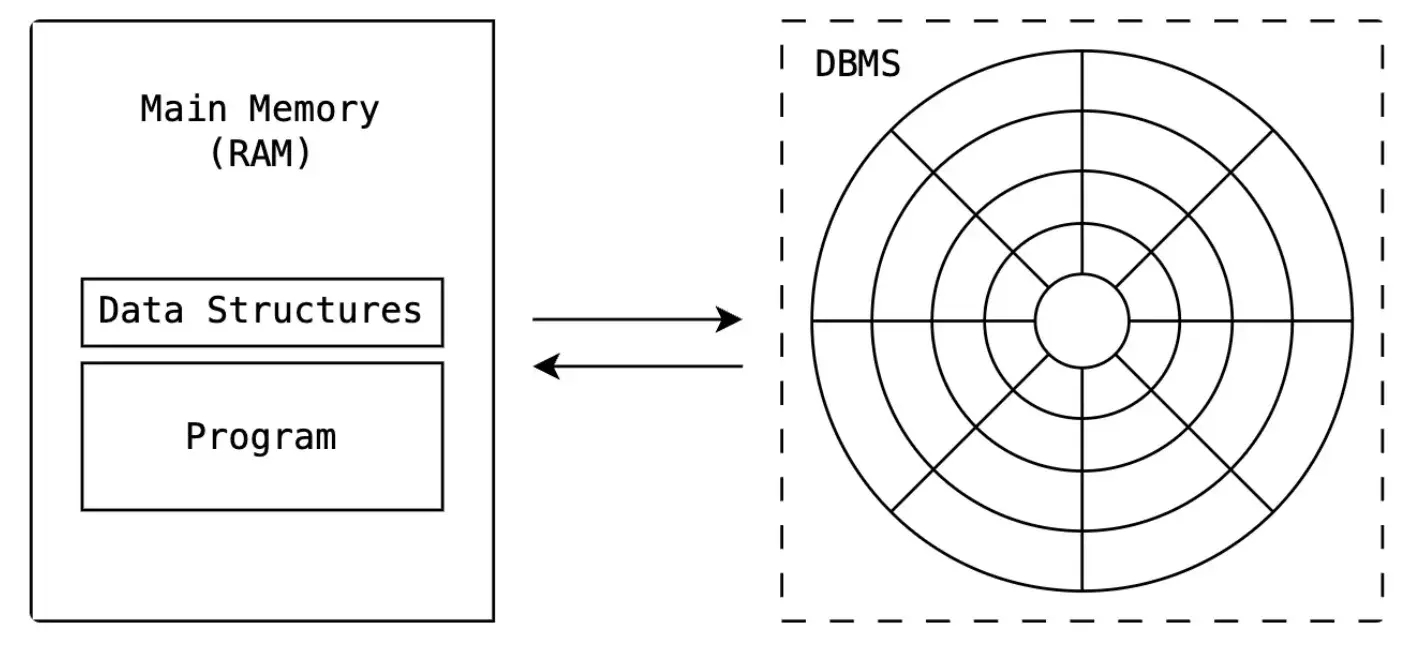

Question: But after accessing the data where are we transferring it and storing it?

Answer: The data that's read (the block/blocks) is first brought into our working memory (RAM). From there, the CPU can process it efficiently. And you might know that inside our working memory, we organize and manipulate that data using data structures. (arrays, hash maps, trees, etc.).

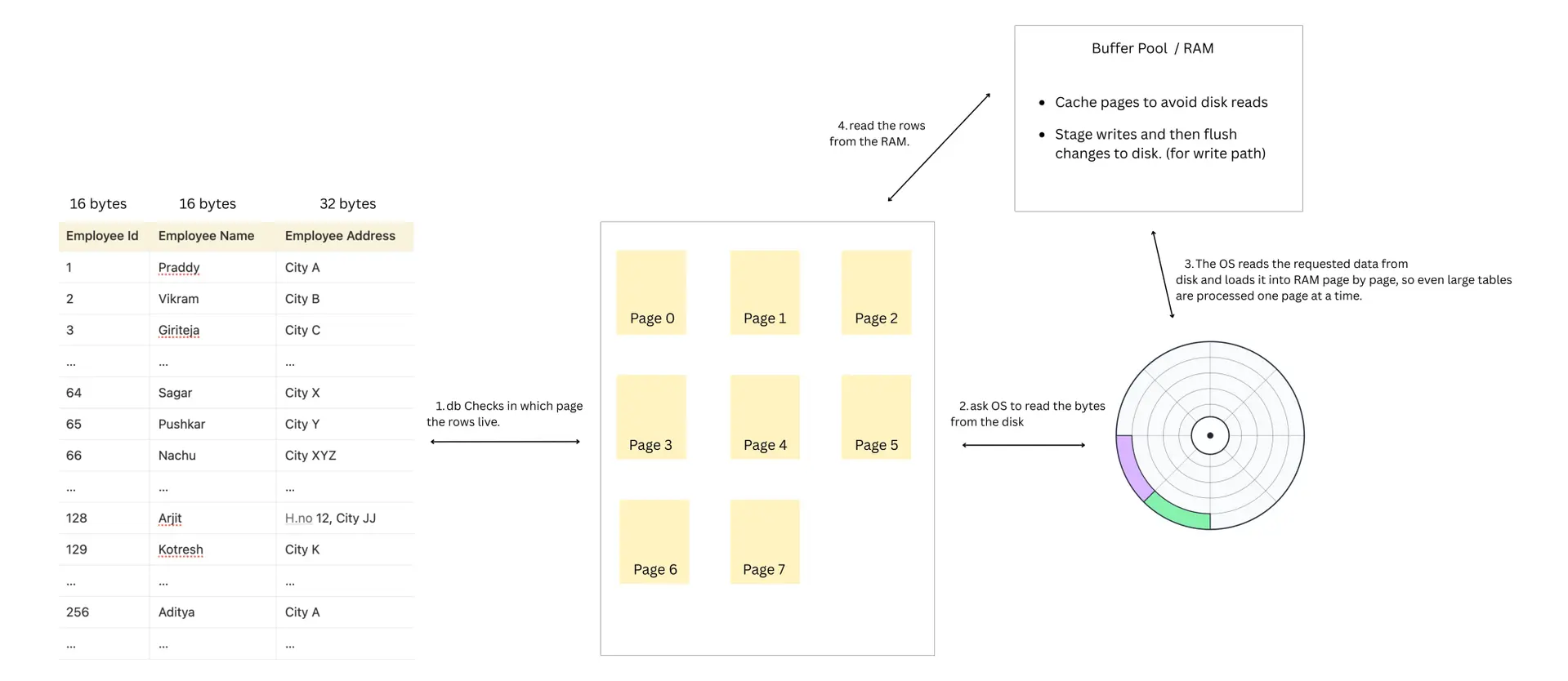

Let's try and put everything together and understand the high level flow of how data flows in and out.

Read Path

- DB finds the page where the rows live and identifies offset on disk for those rows. (If an index exists, the database uses the index to directly identify the page containing the row. If no index exists, the database scans pages sequentially until it finds the row.)

- DB asks the OS to read the bytes from that page file from certain offset till a certain offset.

- OS checks filesystem cache; if missing, OS reads from disk and returns to the db.

- DB places the page into the buffer pool (main memory) and reads the rows from that page.

Write Path

- DB finds the page where the rows live and pulls it into the buffer pool.

- DB updates the row in memory.

- DB writes a journal/WAL entry and persists it to disk

- The page stays in memory and may receive more writes before being flushed back to disk later (reducing I/Os)

- Inserts/deletes follow a similar pattern (details vary)

How data is organized on a disk with an example

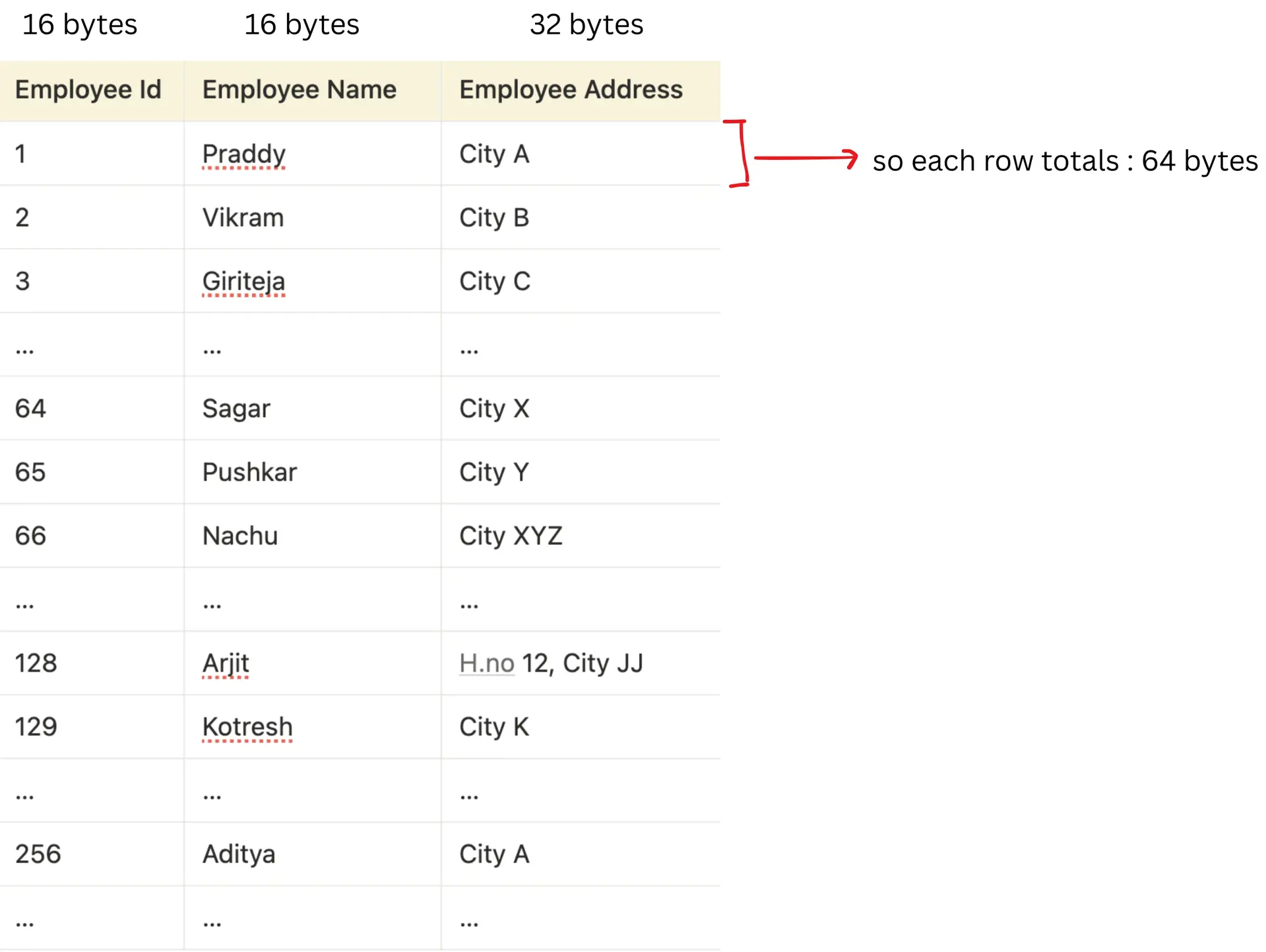

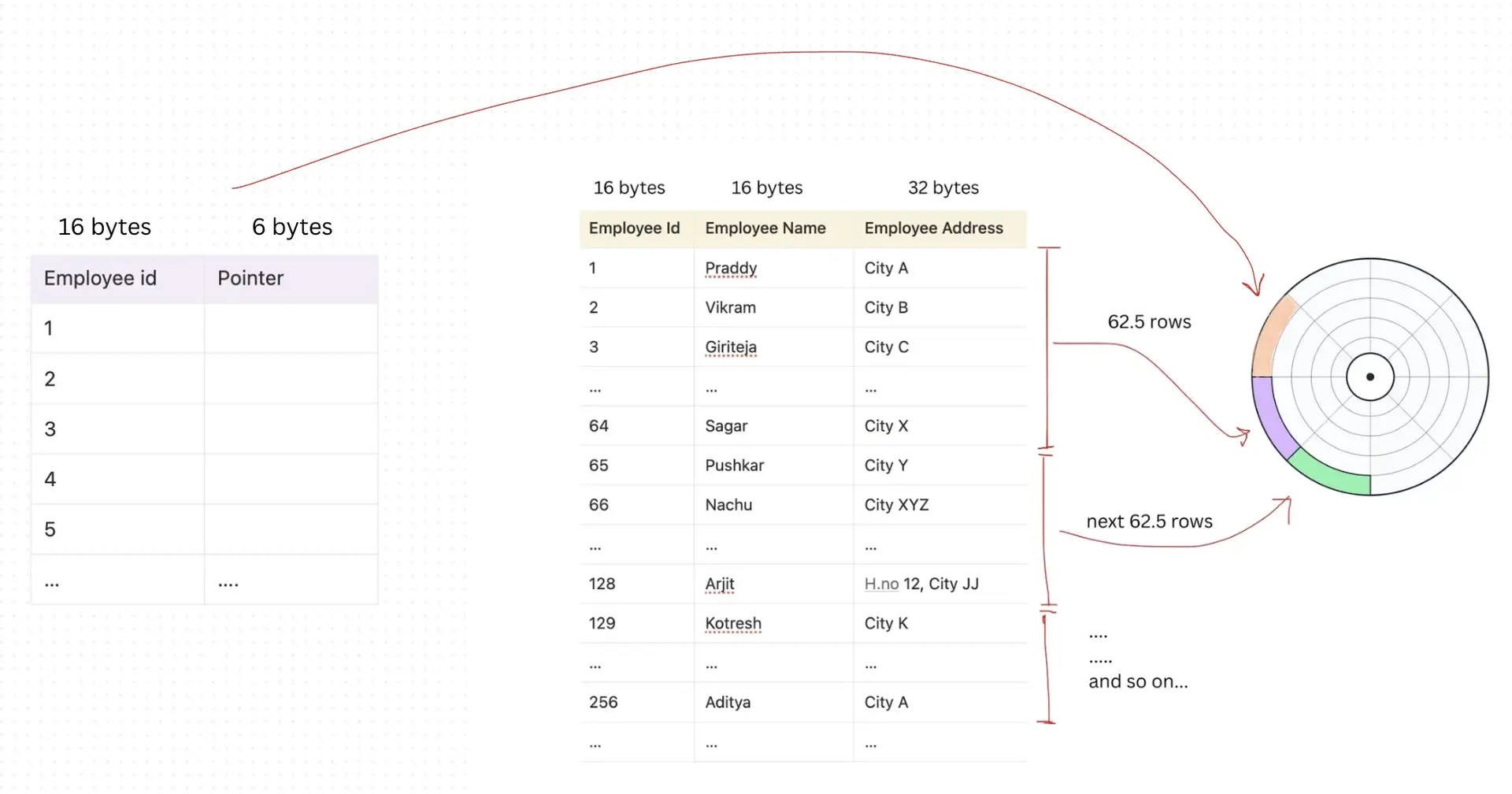

Let's consider our block size of the disk designed by our manufacturer to be 4KB. And the data page size of our database to be 8 KB. And we have a table of employee records containing 1000 records like this:

Employee id → 16 bytes

Employee Name → 16 bytes

Employee Address → 32 bytes

Total bytes of one row = 64 bytes

Now, say if we want to query and return one row (employee_id = 999):

SELECT * FROM employee_table WHERE employee_id = 999;

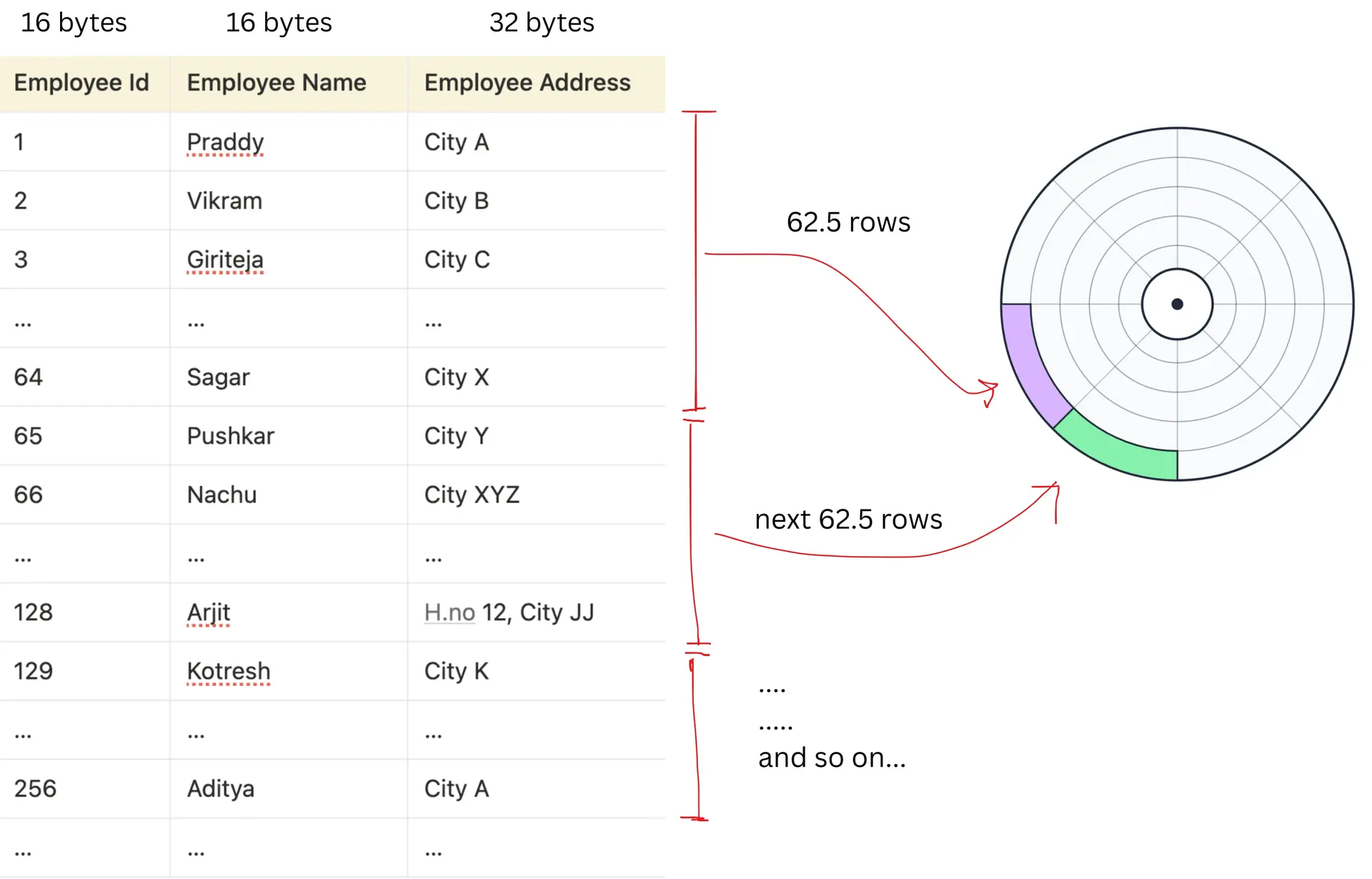

We considered our page size to be 8KB right, with 8060 bytes being the empty record area.

one 8KB page = two 4KB blocks.

But since we are considering only 8060 bytes (as some bytes are taken away by header, and offset.. ), and 1 row is 64 bytes so:

Number of rows in 1 page = 8060 / 64

= 125.93

= 125 rows

So, one page will actually have 125 rows, and not 128 rows.

To cover all the rows, the total number of pages needed would be:

The total number of pages required = 1000 / 125

= 8 pages

Rows are packed into pages; pages are fetched from disk using blocks. In order to fetch 8 pages in terms of OS level blocks:

The number of blocks to fetch 1 page = 8192 / 4096

= 2 blocks

Each 8KB page is stored on disk across 2 contiguous 4KB blocks (meaning these 125 rows are spread across 2 sequential blocks). The OS reads those 2 blocks to get back the data to the page in memory

So searching for employee_id = 999 may require scanning all 8 pages (16 blocks), even though we need only one row.

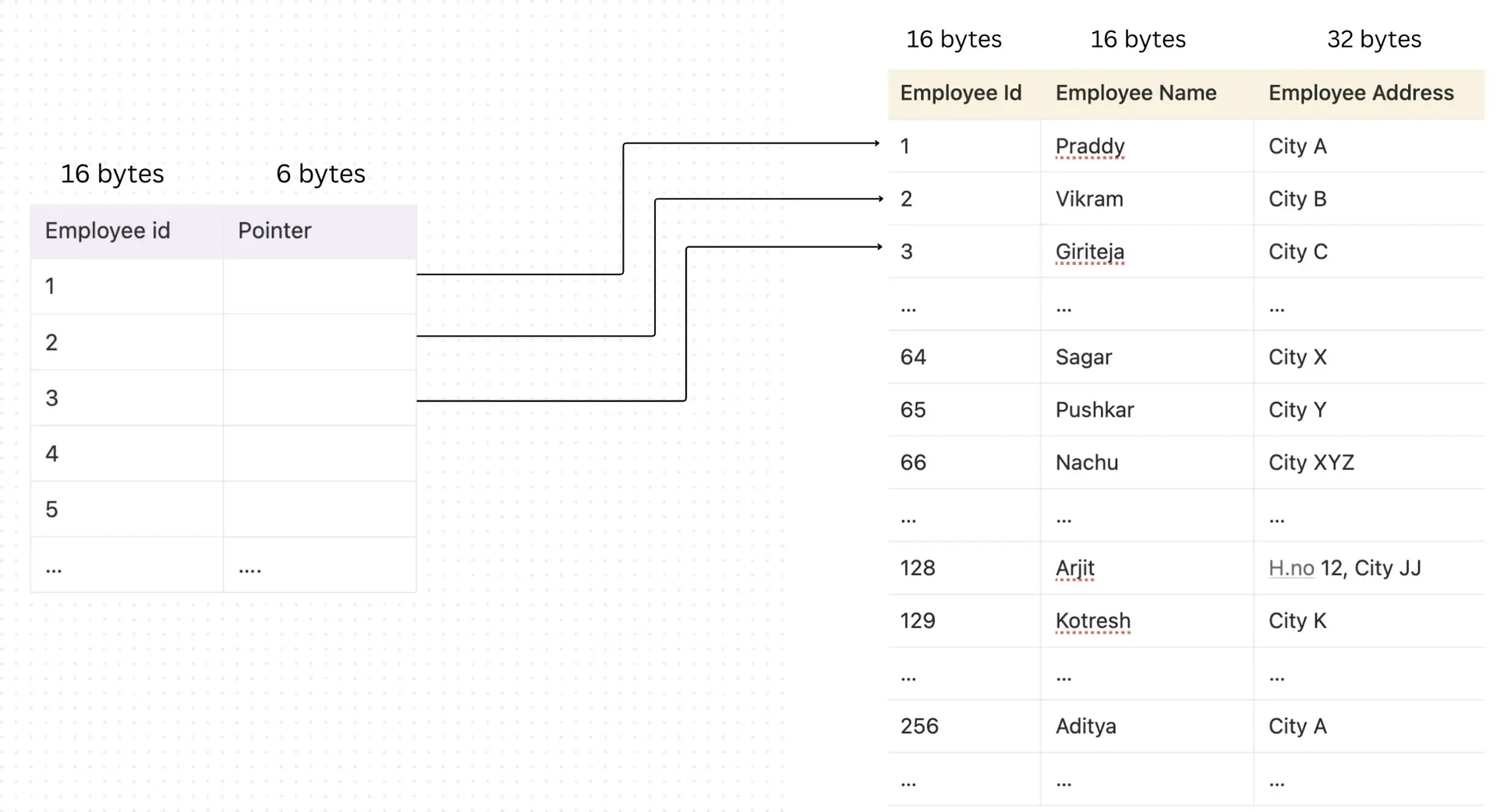

Indexing

Now imagine if we had a table of size 100000, and if we had to find the last record then we had to read all the → 800 pages, that's 1600 OS blocks worth of data to scan. As table size grows, a full scan requires reading more and more pages, which increases I/O cost.

The number of blocks we need to access is directly proportional to the read access time. So we need to reduce the number of block access.

That's where indexing comes in.

Let's index the table on employee id

The next question comes as to where would we store the index table?

The index table also would be stored on the disk.., so how many blocks would it take?

Employee id → 16 bytes

Record pointer → assuming 6 bytes

Total bytes of one row = 22 bytes

The number of rows in one page = 8060 / 22

= 366.3 ~ 367

Number of pages required to cover all rows of the index = 1000 / 367

= 2.72 ~ 3 pages

So the index table would take at most 6 OS blocks.

Now the best part is: to access the index, at maximum we may read 6 blocks (3 pages). Once we find the key, we get its pointer and in a real database that pointer usually does not point directly to the "row object." Instead, it stores something like:

(Page ID, Slot Offset)

Meaning:

- Jump to the correct data page that contains the row

- Use the page's slot directory to locate the exact row inside that page

So after the index lookup, we only need to read 1 data page (≈ 2 OS blocks) to fetch the row.

So the total blocks needed becomes:

6 blocks (index) + 2 blocks (data page) = 8 blocks

So the drastic change we saw is: without index we may read 16 blocks (8 pages), and with an index it may drop to 8 blocks (~4 DB pages).

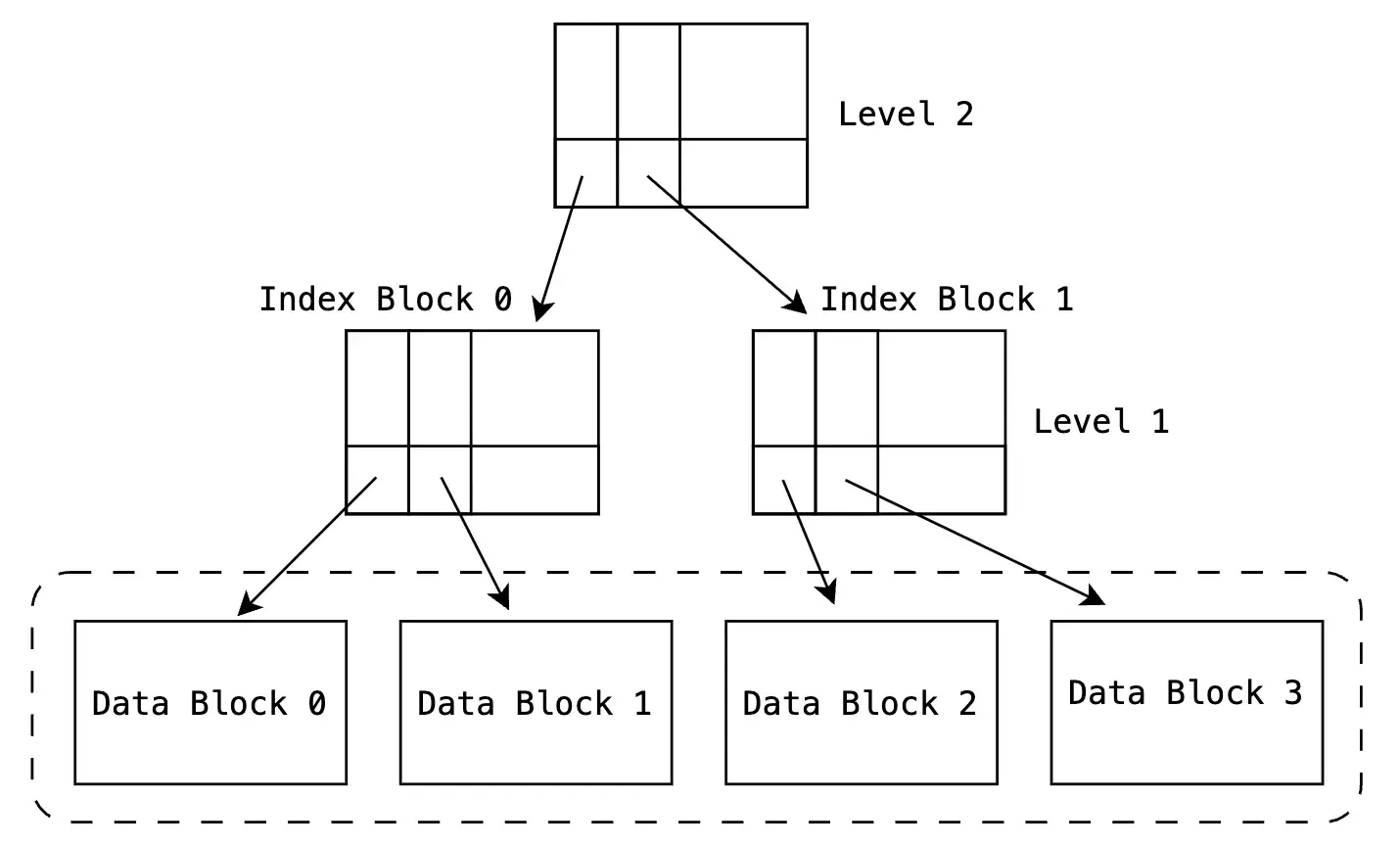

Multi-Level Indexing

So far, our index only had 1,000 entries.

It fit into just 3 pages (6 blocks).

But what if the table had 1 million records?

Now the index would also grow proportionally.

If 1,000 rows → 3 index pages

Then 1,000,000 rows → 3,000 index pages.

That's: 3,000 pages × 2 blocks = 6,000 OS blocks

Now imagine searching for an employee ID inside such a large index. If we had to scan the entire index page by page, we would again be reading thousands of blocks.

So the index itself becomes expensive to search.

So to solve this, we don't scan the entire index.

Instead, we build an index on top of the index. Think of it like this:

We group the 3,000 index pages into ranges.

Then we create a small "guide index" that stores:

- First employee_id in each index page

- Pointer to that index page

Now instead of scanning 3,000 index pages:

- We first read the small guide index.

- It tells us which index page to go to.

- Then we read that specific index page.

- Then we read the actual data page.

So instead of scanning thousands of pages, we now read only:

- 1 guide index page

- 1 lower-level index page

- 1 data page

That's just 3 pages total.

If we keep adding more records, we can keep adding more "guide levels".

This naturally forms a tree-like structure.

Instead of manually managing multiple index layers, databases use a self-balancing tree structure that:

- Automatically grows when data grows

- Automatically reorganizes itself

- Keeps search cost logarithmic

This structure is called a B-tree (or more commonly in databases, a B+ tree). We will talk about B-trees and B+ trees in the next articles.

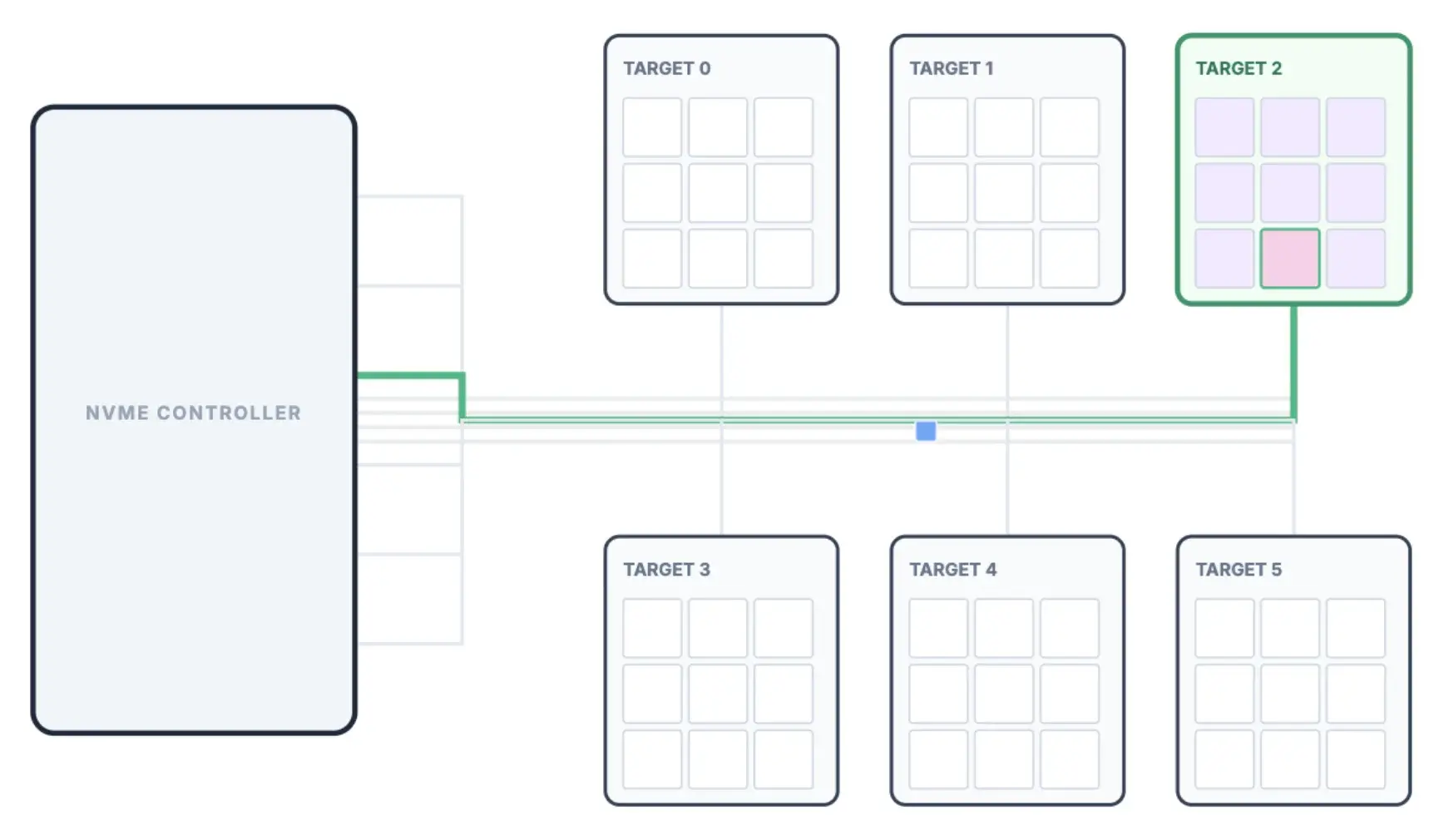

How the data storage in SSD works?

In SSDs, there are no spinning platters. Instead, data is stored across multiple NAND flash chips (often exposed as separate targets inside the SSD) and managed by an NVMe controller (as shown above). The important thing is: even on SSDs, the OS still talks to storage in terms of fixed-size blocks (e.g., 4KB) using logical block addresses.

So when the database requests an 8KB page, the OS issues reads for the corresponding 2 blocks. The NVMe controller then routes those block reads to the correct target / flash chip, fetches the data from the underlying flash pages, and returns the bytes back into RAM. From the database's point of view, the page-based model stays the same only the physical storage mechanics under the hood change.

Hope you liked this article.

If this was useful, subscribe to my weekly newsletter: Evolving Engineer

Support my writing here: buymeacoffee.com/cpradyumnao