How does the database guarantee reliability using write-ahead logging?

December 03, 2025

Series

In Part 1 and Part 2 we saw about ACID transactions and why they form the backbone for any database.

For any database system, reliability is super important.

We keep saying “the transaction commits”… But what actually happens at commit? How does the database make that promise: “Your data is safe now”?

This is where the Write-Ahead Log (WAL) comes in.

1. What “Commit” Really Means

For any database system, reliability is non-negotiable.

When you run a query like:

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 42;

COMMIT;You’re not just asking the database to change a number. You’re asking it to promise:

- This change won’t disappear if:

- the power goes out

- the OS crashes

- even certain kinds of hardware failure happen

That promise only makes sense if the change is safely stored on non-volatile storage (disk/SSD/NVMe, etc.) something that doesn’t lose data even when the machine restarts.

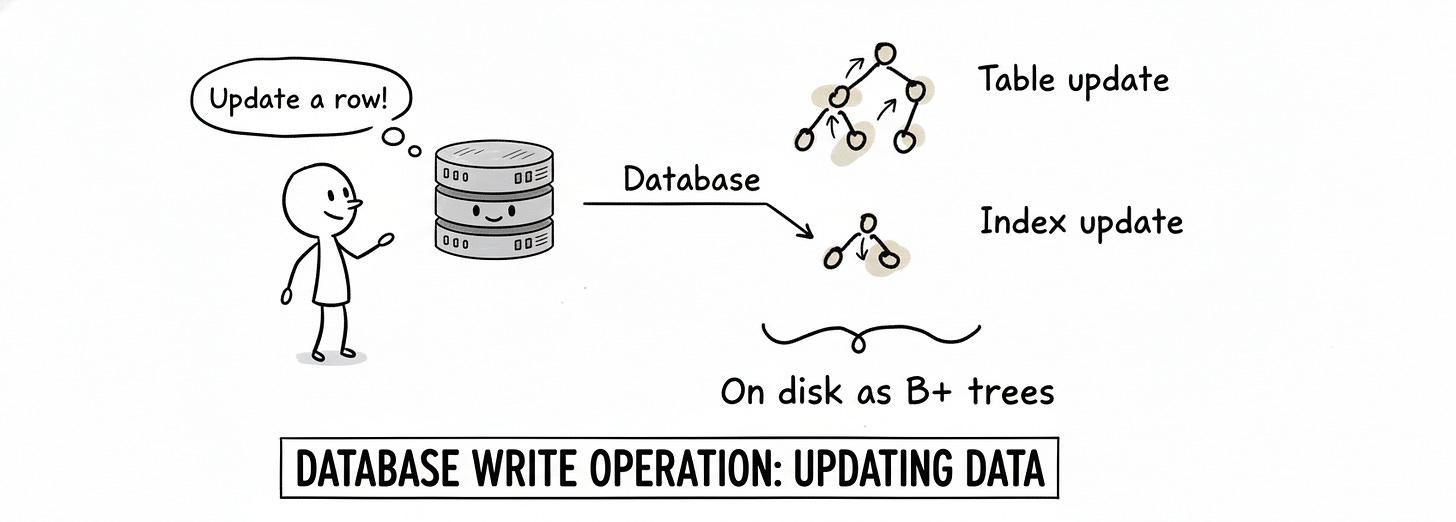

So a naive mental model of commit is:

“At commit, as soon as the row is updated and the transaction is committed, the corresponding blocks on the disk are changed both in the table and in any indexes.”

That’s kinda the right intuition… but it hides a ton of engineering complexity.

Because if we literally updated the data files and all indexes on every commit, we’d be:

- Doing many random writes all over disk.

- Taking a big performance hit.

- Still vulnerable to partial writes in the middle of a crash.

So how do databases stay fast and safe?

2. Enter WAL: Log First, Data Later

The standard trick is the Write-Ahead Log (WAL).

WAL is a standard method for ensuring data integrity. It’s not just used in traditional RDBMS the idea can be used anywhere we care about reliability and crash recovery.

The core idea is beautifully simple:

Before making changes to the actual database files, log those changes in a separate, append-only log file.

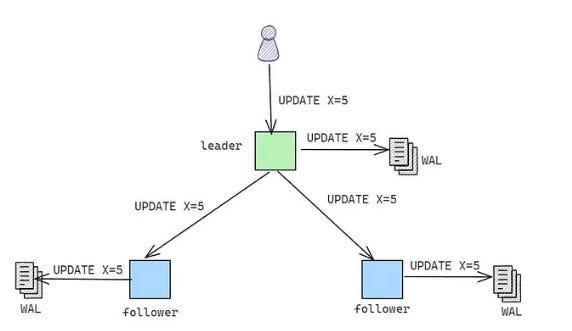

Each node in a database system keeps an append-only log file in persistent storage and every client update sent to the node is first appended to this file (write-ahead) and later applied to the data in the database. This logging technique is called Write-Ahead Logging because the update commands are written to the logs before the actual updates on the data are performed.

Think of them like this:

- The Database: the official, heavy ledger book where you neatly write final balances and long-term records.

- The WAL: a scratchpad where you quickly jot down every transaction as it happens, in order, before you calmly copy them into the ledger later.

Why is this powerful?

- The WAL is a sequential, append-only file. Appending to the end is much cheaper than jumping around updating different parts of tables and indexes.

- Updating the main data files can be done later, in the background.

- As long as the change is safely written to the WAL, the database can say:

“Commit successful and your data is durable.”

So instead of:

“Every commit = update all relevant data/index blocks on disk”

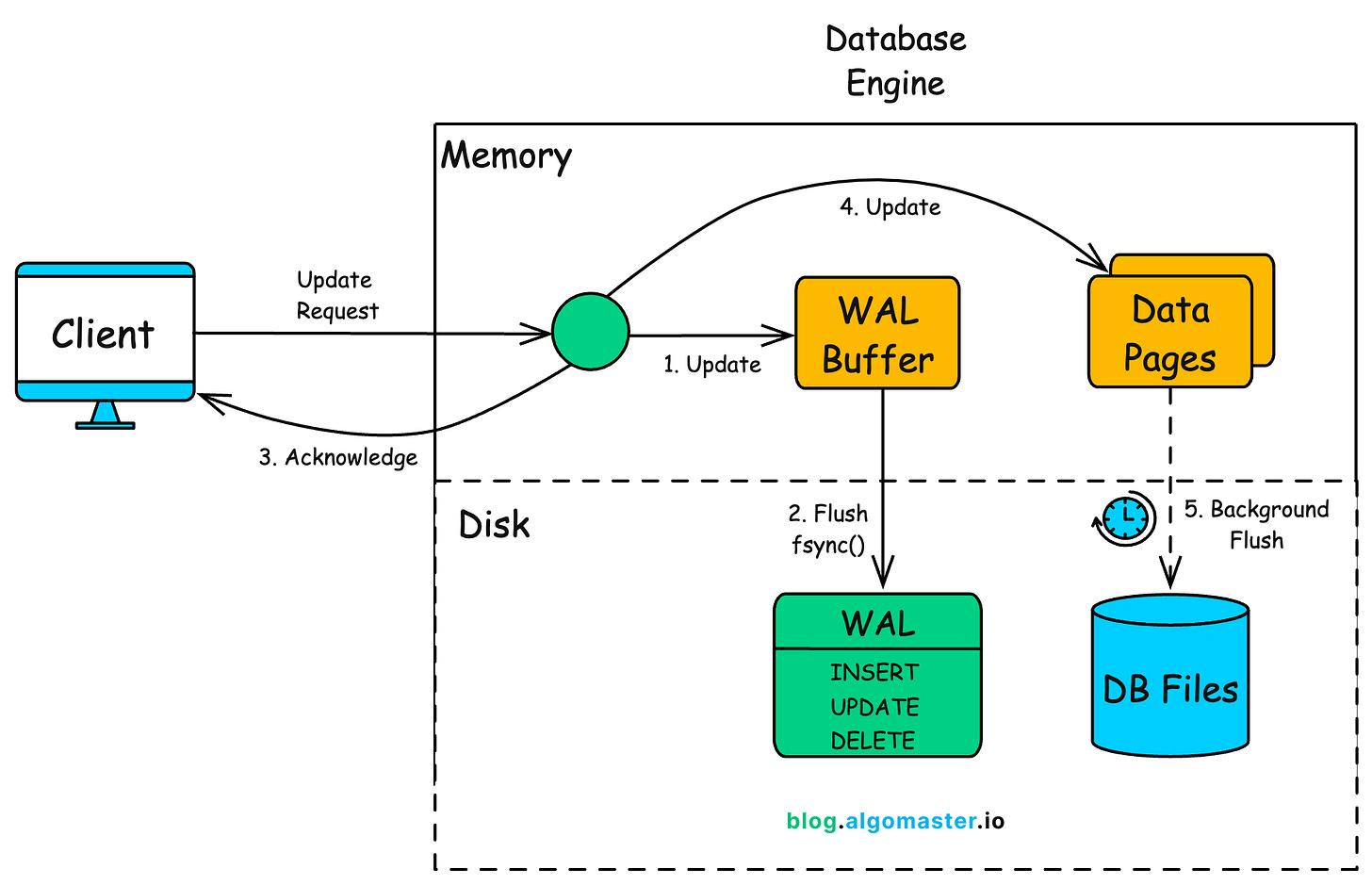

The entire process would look somewhat like this:

- Log the change to WAL (sequential write).

- Flush WAL to disk (ensure it’s persisted).

- Mark transaction as committed.

- Later, apply those changes to the actual data files during a background process (checkpoint).

Writing to the WAL file is not the same as having it safely on disk.

There are layers:

- Your DB writes to its own WAL buffer in RAM.

- OS writes that to the page cache in RAM.

- Only when the OS actually issues a disk write + flush do the bytes land on physical storage.

If the power goes out while the bytes are only in RAM (DB buffer or OS cache), they’re gone.

So on COMMIT, the DB must ensure:

- The WAL bytes for this transaction are forced to disk.

- This is often done with something like

fsync()(or equivalent), which tells the OS: “No seriously, push this to stable storage now.”

Key idea: a transaction is only considered durable when the WAL records for it have definitely hit disk.

3. Advantages of WAL

- Fewer disk writes → better performance (updating table data and indexes directly can mean a lot of random I/O).

- Point-in-time recovery (PITR). In case of failure, can restore a backup of the database.

4. But what if the crash happens while writing the WAL?

Good question and it’s not just theoretical. Imagine we’re appending a record to the WAL:

- The record is, say, 100 bytes long.

- The system crashes after 43 bytes are written.

Now we have a truncated or half-written log record. How does the database know:

- whether this record is valid or corrupted?

- whether it should replay it during recovery?

This is where data protection inside WAL itself comes in.

5. CRC-32: Guarding each log record

Every serious implementation of WAL protects each record with a checksum. A common choice is CRC-32 (Cyclic Redundancy Check).

Rough idea:

- When the WAL record is created:

- The system calculates a CRC-32 checksum of its contents.

- That checksum is stored alongside the record.

- During:

- Crash recovery, or

- Replication (streaming WAL to another server)

- The database:

- Recomputes the CRC-32 of the record.

- Compares it with the stored checksum.

If the checksums don’t match?

- The record is considered corrupted or incomplete.

6. Under the Hood: Segments, Pages, and LSNs

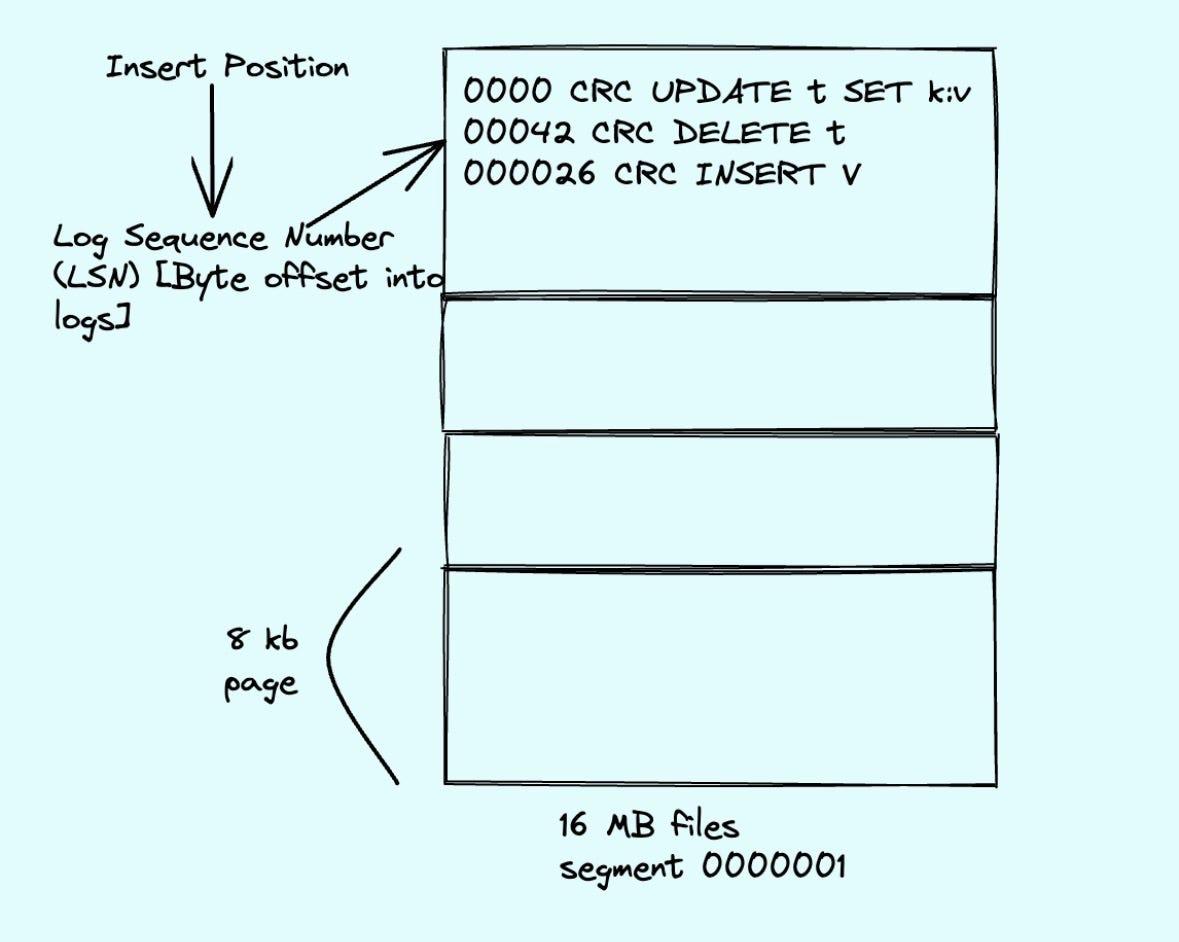

WAL itself isn’t just a single infinitely growing file. It’s usually a set of files on disk.

You’ll often see terminology like:

- WAL segments Each file in the WAL is called a segment. In systems like PostgreSQL, each segment is roughly 16 MB.

- Pages inside segments Each segment is split into smaller pages often 8 KB each. The database writes WAL records onto these pages as it appends data.

This lets the database:

- Rotate old segments

- Archive them for backups

- Delete them once they’re no longer needed (e.g., after a backup + checkpoint)

Log Sequence Number (LSN)

Every WAL entry is given an identifier called the Log Sequence Number (LSN).

It’s not simply 0, 1, 2, 3, ....

Conceptually, it’s like a byte offset into the WAL stream:

- “At this exact byte position in the log, this record starts”

LSNs are used to:

- Track how far the database has applied WAL to the main data files.

- Coordinate replication (e.g., a standby server has replayed up to LSN X).

- Implement point-in-time recovery (replay up to a certain LSN and then stop).

So you can think of the WAL as a big ordered timeline of changes, and the LSN is your precise timestamp on that timeline.

7. How This All Ties Back to Commit

Phase 1: The Active Transaction

- Request: You send an UPDATE or INSERT command.

- Modify Memory (RAM): The database locates the specific data page in its buffer pool (RAM) and modifies it right there.

- Status: This page is now marked as a dirty page because the version in RAM is newer than the version on the hard drive.

- Generate Log: Simultaneously, the database creates a WAL record describing this change (including the LSN - Log Sequence Number).

Phase 2: The Commit (Durability)

- Request: You call COMMIT.

- Prepare WAL: The database calculates the CRC-32 (checksum) for the log records.

- Flush WAL to Disk: It forces only the WAL records (up to the current LSN) to be written physically to the disk.

- Note: The main data file on the disk is still old. The new data exists only in the WAL (on disk) and the dirty page (in RAM).

- Acknowledge: The database tells you: “Commit successful.”

Phase 3: The Background Checkpoint (The Dirty Page Flush)

This happens asynchronously, minutes later, or when the log gets too big.

- Identify: The checkpoint process looks at the buffer pool for dirty pages (pages modified in RAM but not yet on disk).

- Flush Data: It writes these dirty pages from RAM directly to the main table/index files on the disk.

- Sync: It ensures these data file writes are physically synced to the hardware.

- Truncate Log: It marks the WAL segments prior to this checkpoint as recyclable or ready for archive, because that data is now safely inside the main data files.

Phase 4: Crash Recovery (If the plug is pulled)

Scenario: The power failed after Phase 2 (Commit) but before Phase 3 (Checkpoint).

- Restart: The database engine boots up.

- Locate Checkpoint: It reads and finds the LSN of the last successful checkpoint.

- Logic: “Everything before this LSN is guaranteed to be in the data files. I can ignore it.”

- Scan Forward: It reads the WAL files starting from that checkpoint LSN up to the end of the log.

- Verify: It checks the CRC-32 of the log entries to ensure the crash didn’t corrupt the last half-written log line.

- Redo (The Replay):

- It sees a committed transaction in the WAL.

- It checks the data page. The page has an older LSN (because the RAM was wiped out).

- It applies the change from the WAL to the page to restore the data.

- Undo (The Rollback):

- It sees a transaction in the WAL that started but has no COMMIT record.

- It discards those changes to ensure consistency.

I know this article felt like too much words, and less visuals. But the topic is such, I had to cover everything that happens behind the scenes.

Hope you got a fair understanding of WAL and how databases manage the heavy lifting for us behind the scenes.

If you want more such powerful and extremely informative content right to your inbox, then please do Subscribe to my weekly newsletter!